Kraków Part 1

To begin the Kraków installment of Ramblelogue I could rattle through the former Polish capital’s myriad must-sees: its UNESCO World Heritage Site Old Town, Europe’s largest market square, Wawel Castle, the Jewish Quarter, church after church, museum after museum, the gothic-followed-by-the-renaissance-succeeded-by-the-baroque of its architecture. All mightily impressive, all an understandable draw, and all worthy of the many tomes written about them. Over two visits in quick succession (with a brief interregnum in Zakopane) I love visiting each of these sites of renown, but they aren’t what make me fall in love with Kraków.

Rewind a fortnight: my first post was a (failed) attempt to capture the dualities – the contradictions and tensions – that I spot in Berlin. Perhaps there’s something of the same with Kraków: an awe-inspiring city with a terrible history; scarred beauty; welcoming hosts despite (because of?) past traumas.

Prior to my arrival, I was in need of something easier on the eye. The 7-hour train from Prague’s Hlavni Nadrazi was comfortable enough as it crossed rivers dappled with metallic camouflage, stopping at drab, near-deserted provincial stations. At one stop, I forget which, an amiable Czech couple join my compartment. At the next stop our travelling party gains a plus-one; however, whereas on the way to Prague I’d been joined by that Elle Fanning lookalike, I’m now joined by Meatloaf’s character from Fight Club (a cheap shot, but an accurate comparison). Opening his first can of Budvar at 10am and promptly spilling it all over my legs, he is at least very genial and attempts conversation before realising that neither of us speak each other’s language.

Arriving at Kraków Główny (main station) in mid-afternoon, I walk the mile-or-so to my hotel on the western edge of the old town – the wheels of my luggage sounding a satisfying clip across the well-worn flagstones. For lovers of medieval and early modern architecture, there is eye candy in every direction. I’m instantly smitten.

View over the Vistula River, Krakow

My hotel’s receptionist Tomasz manages a rarefied combination of professional authority and cordial buddyness. When I ask him for help with a few basic Polish pronunciations – not easy for the English tongue – he tells me with a wry grin “we are not Russian, we don’t mind how you pronounce it”.

Indeed, Kraków is only 170 miles due west of Lviv, and Russia’s ongoing illegal invasion of Ukraine has made its mark here. Each evening in the main market square (Rynek Główny) an amateur choir sings Ukranian hymns to raise funds for medical care in their battered homeland; on several occasions I’m stopped by money box-wielding students asking for contributions towards similar causes; the yellow and blue of the Ukranian flag is as common a sight as the red and white of Poland’s. Back at the hotel, Tomasz tells me that thousands of Ukranians have been welcomed by Cracovians after having fled their homes.

This is the theme that I begin to attach to Kraków: sanctuary.

The most obvious historical example is Oskar Schindler’s Enamel Factory where, during Kraków’s six-year occupation by the Nazis, Schindler provided sanctuary to hundreds (possibly thousands) of Jews, mostly from the nearby ghetto, by employing them in his factory and thus preventing them from being interned to the extermination camps.

Made famous by Steven Spielberg’s 1993 classic Schindler’s List (adapted from Thomas Kenneally’s 1982 Booker winning Schindler’s Ark), the factory building is now home to the Historical Museum of the City of Kraków and the Museum of Contemporary Art in Kraków. Both are first-class.

I felt a palpable tension as the story told in the Historical Museum began with first-hand accounts from late-summer 1939 of the looming German invasion. The fears of everyday Cracovians are starkly illustrated in the diaries, letters, and newspaper articles on display, soundtracked by local radio reports of the Nazi hordes assembling on Poland’s borders.

Progressing in chronological order, exhibits include enamelware made by the Jewish workforce and a reproduction of Herr Schindler’s workspace. The Nazi’s eventual defeat brings the exhibition to a close, but upon exiting the museum we are reminded by a huge Big Brother-esq poster of Stalin of the next dark epoch in Kraków’s biography.

Oskar Schindler’s Enamel Factory, Krakow

I was unsure whether the next-door Museum of Contemporary Art would be an appropriate fit with what I had just experienced, but I was pleased to be proven wrong. Many of the pieces on display take nationality, migration, and identity as a theme – appropriate to the gallery’s location.

Two video installations grip me (with apologies to the artists for my failure to record their names): the first featuring a group of Polish Neo-Nazis being filmed watching and discussing footage from gay clubs, of trans men and women, and of immigrant communities; the second focussing on protests against former-Prime Minister Donald Tusk’s calls to remove crucifixes from the country’s parliament and schools.

The theme of sanctuary returns when one afternoon I enter the 14th Century ‘brick gothic’ St Mary’s Basilica (Kościół Mariacki). Despite my atheism (Humanism, to be precise), I’m a sucker for church architecture, particularly gothic, and the interior of St Mary’s stops me in my tracks. In fact, it brings me to such a halt that once I take a pew I spend over an hour in quiet contemplation here, longer than I can recall spending in a place of religious worship.

The red brick edifice stands proud with cornices gilded in gold and black; the nave ceiling a sumptuous lapis studded with gold; the ornate altarpiece claims my gaze as if it were a cinema screen.

St Mary’s Basilica, Krakow

Perhaps it is inevitable that a city that has been sacked by the Mongols, pillaged by the Swedes, ravaged by bubonic plague, partitioned by the Prussians and Russians, occupied by the Nazis and controlled by Communists would develop an intuition for sanctuary.

I have, of course, experienced Kraków’s embrace very differently, but few other cities have made me feel so instantly welcome and at home whilst simultaneously in awe.

Auschwitz

1,300,000 human beings were not afforded any sanctuary when they were sent to Auschwitz and the neighboring Auschwitz ii-Birkenau and iii-Monowitz; 1,100,000 were murdered there.

Those figures are unfathomable. So, too, is the figure of 6 million Jews murdered by the Nazis and their enablers during the Holocaust, or Shoah.

There is very little that I find myself able to write about my visit to Auschwitz – that being because I found it so profoundly moving and so deeply incomprehensible that I struggle to articulate my thoughts.

The torture, indignity, sickness, the agony of the victims…the psychopathy and pure evil (the banality of evil) of the Nazi regime…my belief is that it is not my place to write about my visit but it is instead my responsibility to learn, to pay respect, and to think deeply about what happened. Collectively, we are responsible for proactively ensuring nothing like this ever happens again, including preventing the several examples of genocidal ethnic cleansing taking place around the world today.

A visit to the twin-sites isn’t merely a ‘must see’: it is essential. I would simply urge readers to go out of their way to visit and to take a guided tour (I consider my knowledge of WW2 and the Holocaust to be good but still I benefitted from my group’s excellent guide, herself a resident of the Polish town of Oświęcim, from which Auschwitz took its German name).

Buses to the site entrance from Kraków and other regional cities are frequent and affordable. Book your visit in advance via https://visit.auschwitz.org/?lang=en.

Krakow Part 2

Returning to Kraków following a brief diversion to Zakopane, I gravitate towards the neighbourhood of Kazimierz. Sitting between the south-eastern corner of the Planty Park (the pleasant ring of parkland following the foundations of the old city walls) and a crook of the Vistula River, Kazimierz was a separate city in its own right from the 14th until the 19th Century. For much of its history, it was home to a large Jewish community until the Nazis forcibly moved most of the population across the river to the Jewish Ghetto they had established in Podgórze.

Despite the bombardment the area suffered during WW2, modern Kazimierz retains much of its historic character. A small but visible Jewish population has returned, but is now joined by a more visible hipster population: this could be Kraków’s Hackney or Brooklyn. Filled with vintage clothing boutiques, art stores, graffiti-covered drinking dens, even street-side ‘weedomat’ cannabis vending machines, I like the place.

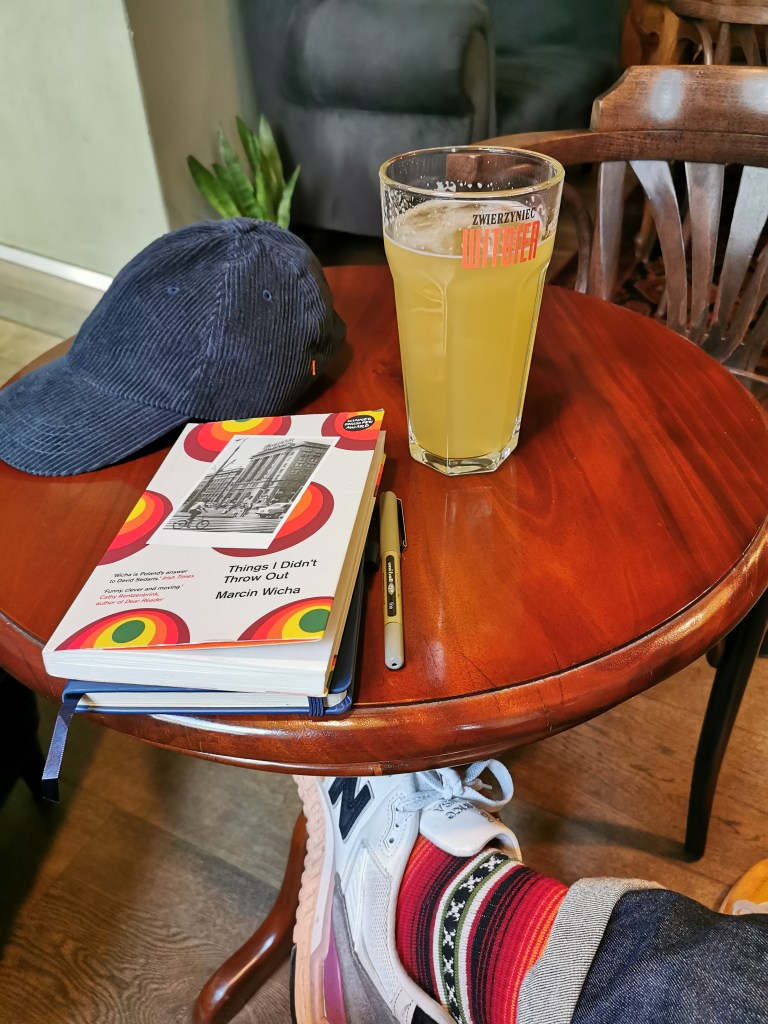

Talking of drinking dens, I’m reliably informed (and decide that I should independently verify) that central Kraków has the greatest concentration of bars anywhere in the world. Fortunately, my fear that this would turn the place into a Brits-abroad-stag-do-hellscape is abated when I find that most of the city’s boozers thrum to a beat quiet enough to accommodate book reading in tandem with wheat beer sipping.

It is in one of Kazimierz’s tiny corner bars, glass of Zwierzyniec half-full, that I learn the sad news of the passing of Hilary Mantel, a literary hero.

My remaining 48 hours in Kraków are spent meandering quiet cobbled streets, looking up at elegantly decaying/decayingly elegant facades, dodging the odd clunky old tram.

Na Zdrowie, Hilary! Na Zdrowie, Kraków! I hope to return someday.

“History offers us vicarious experience. It allows the youngest student to possess the ground equally with his elders; without a knowledge of history to give him a context for present events, he is at the mercy of every social misdiagnosis handed to him.” Hilary Mantel, 2009.

Na Zdrowie!

Leave a comment