Gdańsk is an artist’s dream. Its waterfront a haven of activity, primed for a watercolourist in carmine, vermilion, chestnut, cinnamon, cream and brick. Akin to Bruges or Amsterdam, it suffers from a similar deluge of tourists (says the tourist), noticeably attracting budget airline weekenders. I hear more British accents here than anywhere else in Poland.

It’s also a historian’s dream. The first shots of WW2 were fired at the city’s Westerplatte peninsula from the German battleship Schleswig-Holstein’s position in the Baltic. Six years later, what was once the Free City of Danzig lay virtually flattened.

In previous centuries it had required the protection of the Teutonic Knights, based 50km south at Malbork. In turn, it has been attacked by Brandenburg, annexed by the Prussians and Napoleon, and repeatedly regained its freedom. Membership of the Hanseatic League brought more prosperous times.

Part of the ‘Tricity’ with neighbouring Gdynia and Sopot, the Gdańsk of today is Poland’s busiest seaport and its sixth largest city, home to half a million.

Arriving at Gdańsk Główny (main station) after dark and navigating the streets of the old town whilst wheeling my luggage in tow, being surrounded by my favourite combination of cobbles and gothic-renaissance architecture immediately fills me with optimism, especially with the city so splendidly lit. Dumping my bags at my supposedly conveniently located hotel on Długa, I head straight back out to enjoy the evening ambiance. But my optimism for the city quickly sinks thanks to tout after tout pestering me to eat at their restaurant, drink in their bar, ogle in their strip club – the touts for the latter being especially vulgar.

The action centres on Długa, the ‘royal route’ along which visiting monarchs would once parade. The architecture reflects that regal status, although, as with many Polish cities, it is important to remember that so much of Gdańsk was rebuilt brick-by-brick after the destruction of WW2. The difference here is that much of the rebuilding was completed in the Polish style in an attempt to erase the memory of the two centuries-long Prussian dominion over what was then Danzig.

Tourism reigns here now, it seems, in this city that was home to the “first authentic workers revolution”, as Adam Zamoyski puts it in his biography of Poland. It was from the shipyards of Gdańsk that Lech Wałęsa led the Solidarity movement, which was so instrumental in the opening up of Poland to the democracy that it is today, taking the country with him from its rusting slumber, hidden behind the iron curtain, to its modern ‘economic miracle’. But today, the casual visitor is forgiven for missing the city’s port and heavy industry, which lies mostly to the north of the historic centre, closer to where the Motława River flows out into the Baltic Sea.

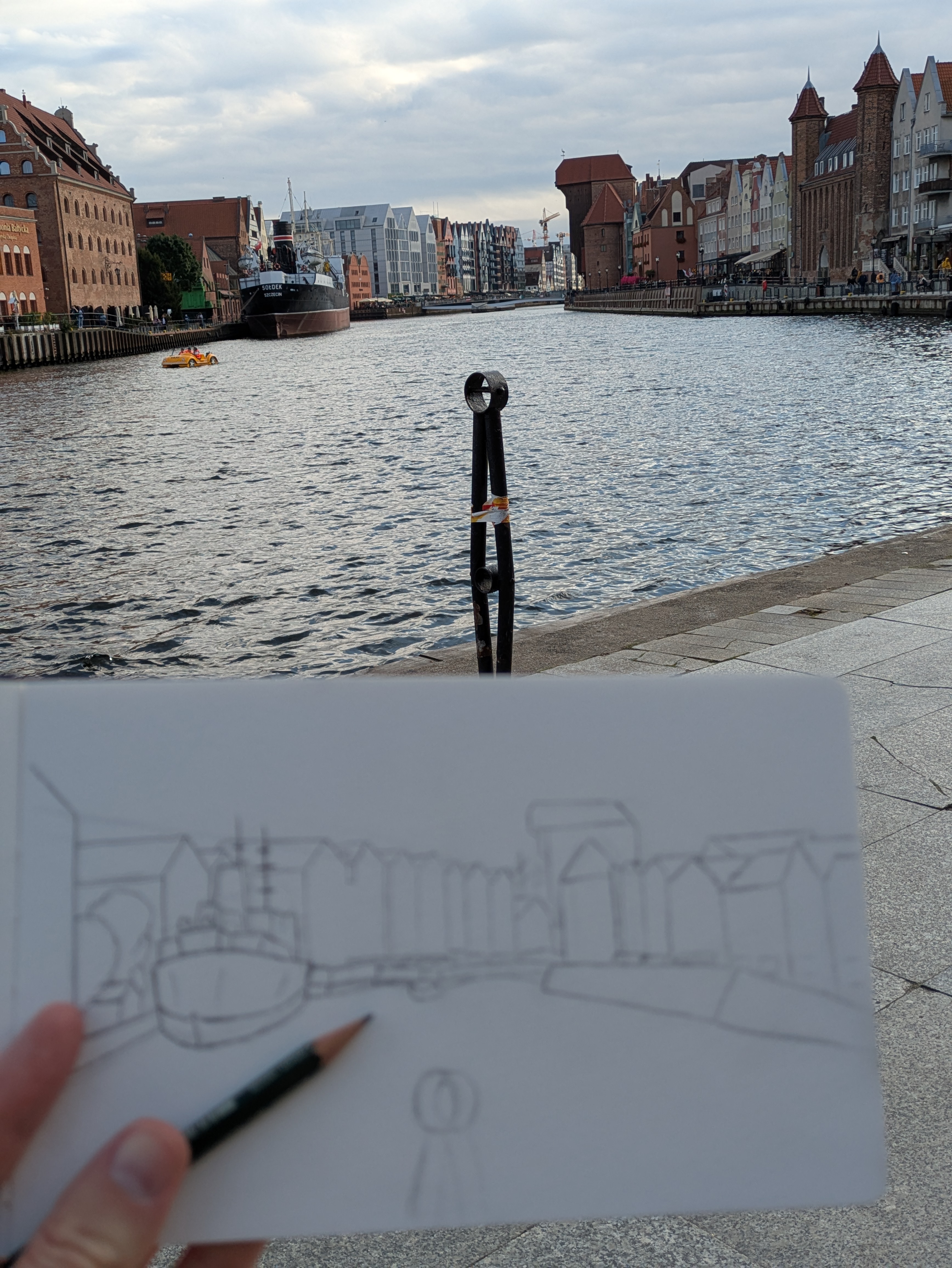

(Above: St Mary’s Church inside and out. Top: Długa and pausing to sketch the waterfront)

Despite its immensity, St Mary’s Church (the diocese’s co-cathedral) is almost concealed from view at street-level, such is the height and density of the townhouses that line the streets of the Old Town. One of the world’s largest brick churches, suffice to say that St Mary’s is a humdinger, notwithstanding its air of austerity – a minimalist look to its outer shell, even with those maximalist windows of some 50ft high, and the plainness of its forest of massive white pillars inside. So seriously impressive that I’ll even forgive it for its lack of flying-buttresses, that feature of sacral architecture that I love so much.

The size of those windows floods the nave with light and space, despite how densely packed those enormous pillars are. The most impressive of St Mary’s internal features is the 15th Century astronomical clock, an audacious feat of precision engineering, animating the time, date, zodiac, and Saints’ days through a series of illustrations and marionettes. Elaborate and intricate, the clock stands in contrast to the solid simplicity of the church.

(Above: St Mary’s astronomical clock and the streets outside the church)

Avoiding the throng by disappearing into the grid of streets off the main tourist drags, good cafes and decent eateries start to appear, far quieter than the mediocre chains found along Długa.

Desperate to avoid such mediocrity, a short walk north of the historic centre, Gdańsk’s must-see is its Museum of the Second World War. Built in 2008, I found the angular building itself somewhat ugly, but it’s what’s inside that counts, and the visitor’s experience is exceptional. An excellent audioguide takes the visitor from a recreation of a Polish street circa 1939, through dozens of exhibits on a diverse range of personal stories of the war, all the way to the ruins of Poland in 1945.

I don’t recall ever seeing such detail on the subject, or any single subject, for that matter. The size of the museum allows for the most comprehensive of looks into the scale and breadth of the Nazi atrocities, and those of the Soviets, even lifting the lid on war crimes committed by the puppet regimes in countries such as Yugoslavia. Despite a broad knowledge of WW2, I came away having learnt so much, and seeing the conflict through a Polish perspective was invaluable. Genuinely moved throughout, I left in a silent mood.

(Above: The Museum of the Second World War – plan to spend a day here)

Taking the No.8 tram to the seaside suburb of Jelitkowo (less than a quid) is an opportunity to see everyday Gdańsk. Commuters and shoppers hop on and off, mums drag toddlers aboard and plonk them two to a seat, happy feet dangling over the edge. Smooth and steadily the tram winds through the northern suburbs, past row after row of dull, square tenement blocks, walls occasionally enlivened with bright spray paint murals. There are notably few houses. Networks of overhead walkways link communities. Nearer the Baltic beachfronts, newer, clearly more expensive blocks pop up. Clean white concrete and glass replaces drab beige prefabricated roughness; aesthetic form replaces dated functionality.

Gdańsk’s northern fringe is blessed with miles of clean, sandy beach, the gunmetal grey Baltic almost merging with a sky of the same colour. The tide is gentle, and tempts me to dip my trainers in. The beach runs unbroken from Jelitkowo to Brzeźno, enabling a peaceful walk with the peninsular of Westerplatte in the distance: the calm of the scene belying the history of this location where the world’s most devastating conflict was ignited, perhaps an apt analogy for travelling in Poland.

Parallel to the beach runs a paved boardwalk, clearly beloved by runners and cyclists. Adjacent to that, pine woodland. I can never resist walking under pine trees – that smell and the spongy bounce of the carpet of moss and fallen needles. My only accompaniment, the sound of the sea and the ‘tchack-tchack’ of jackdaws as they strip bark from the trees in search of lunch.

Arriving at the Brzeźno end of the beach, I find a bench that has sunk so deep that, taking a seat, my arse is just 2″ above the fine sand. That pine scent has been replaced by the familiar smell of the sea. Young seagulls land next to me, stoney grey wings matching the colour of the horizon. Rather apologetically, they begin exploring their arena, pausing and tilting their heads as if listening to the conversation of passing dog walkers.

Sinking deep into thought on that sunken bench, it occurs to me that whenever I visit a British seaside town I end up with Morrissey’s ‘Everyday is Like Sunday’ in my head (“every day is silent and grey”), but they really did bomb this seaside town. Armageddon did come.

Before heading back into Gdańsk, I find a beachside bar for a quiet pint and take out my sketchpad (“hide on the promenade, etch a postcard”), tinged with a hint of regret that I’ll soon be back among the multitudes on Długa.

Malbork Castle

The Castle of the Teutonic Order in Malbork, to give its full title, first comes into view as the train from Gdańsk skates across the bridge over the Nogat River. Completed in 1406, Malbork is the world’s largest castle by area. This is a proper castle.

Stepping down from the carriage at Malbork station, the smell of roasted corn hangs in the air, presumably emanating from the massive processing plant over the road. The entrance hall to the station nods to the behemoth UNESCO World Heritage Site that the town of the same name serves – a smart red brick space adorned with shields from the regions that fell under the protection of the Teutonic Order.

Spread out on its strategic position along the banks of the gently flowing Nogat, the castle’s enormity is a challenge to describe. Its footprint, some 52 acres (I put that at around 35 football pitches), is four times that of Windsor Castle. It was home to over 3,000 knights, soldiers and squires, and remains the largest complex of brick buildings in Europe.

Despite its size, Malbork’s location in this corner of Eastern Pomerania meant that it would always be prized by the region’s power-brokers as they sought to control access between the Baltic and the Polish interior. The fortress was captured and changed hands several times through its 600 year history, including by the Teutonic Order, then the Polish kings, the Swedes, the Prussians, and, in 1939, the Nazis. A panoramic photo by the ticket hall shows the damage their industrialised weaponry inflicted.

Today, it’s Malbork’s turn to capture the imagination.

Entering under the lethal-looking portcullis, the tourist’s route takes in great hallways, armories teeming with weapons brutal and vicious, the Grand Master’s bedroom, kitchens, room after shadowy room, and up to the High Castle. As expected for the home of a Catholic order, St Anne’s Chapel provokes hush, all dimly lit by candle chandeliers. An exhibition on amber – a key early trade in this part of the world – takes up one large hall.

Standing below the inner walls portrays just what a challenge Malbork must have been for invading armies to take. Laying siege must have been agony for both sides. Far easier to take the 10.02 from Gdańsk.

(Below and above: Malbork Castle)

Leave a comment